Image by pikisuperstar on Freepik

Science of Chess: What does it mean to have a "chess personality?"

What kind of player are you? How do we tell?The academic year began a few weeks ago in North Dakota, which means I've been busy with the Neuropsychology course I teach during the fall each year. The big goal I have for my students is to learn how to think about relationships between the mind and the brain. What kind of data do we need to decide that a part of the brain contributes to some mental process? What is our best understanding of how different aspects of the mind are linked to specific parts of the brain? There are deeper questions I try to get them thinking about all semester, too: Can we use the organization of human cortex in functions as a way to understand what the pieces of our behaviors, our experiences, and our minds are? We cover a lot of topics that my students usually find intriguing like amnesia, aphasia, prosopagnosia, and a wide range of other patient outcomes that have helped us understand the cortical organization of behavior and experience.

One key question we have to return to multiple times during the term is the question of how best to characterize different aspects of cognition and behavior. How do you measure the mind so that you can try to link mental processes to the brain? That question can seem easy to answer when we want to measure the limits of someone's memory, but it quickly becomes apparent that a lot of intuitive, everyday experiences and tasks are more challenging to turn into a number. To get my students thinking about these issues early in the term, I usually introduce them to some tools for measuring the mind that are informal, but also a lot of fun.

Random Internet Quizzes, Psychometric Validity, and Personality

I am a total sucker for a good internet quiz. I would love to find out what country I should visit next, which movie sidekick would be my ideal brunch buddy, and the dessert that most closely matches my aesthetic. (In order, Japan, Chewbacca, and Ebelskivers). These quizzes aren't serious, of course, but they're as fun as they are because we sort of care about whether or not the answers match whatever intuitions we have about these things. If I take a "Which Disney Princess Are You?" quiz and get any answer besides Belle, I am MAD.

By http://static3.wikia.nocookie.net/__cb20120627060108/disneykilalaprincess/images/5/53/Belle.png, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41755941

For my students, I use these to get them thinking about a key psychometric concept called validity. A simple way to think about what this means in the context of trying to measure some aspect of the mind is that the validity of a test or scale refers to how well we are measuring what we intend to measure. Measuring your memory by asking you to jump rope clearly has poor validity, for example, but measuring your spatial cognition by asking you to do a mental rotation task seems alright. A question I ask them to think about with regard to these quizzes is how they'd try to establish the validity of the sillier ones: Can you come up with a way to find out if a quiz came up with the right Disney Princess? What exactly would it mean to be wrong?

These frivolous quizzes are a gateway to talking about other aspects of the mind that we have strong intuitions about, but that are also difficult to measure. Specifically, it's not a big leap at all from Disney Princesses and brunch buddies to something most of my students are both very interested in and have strong feelings about: Their personality. Look, we all know what personality is, right? People are the way they are and that "way that they are" is what we mean by the word personality. Some people are nice, some people are not-so-nice, some people are "quiet types", and so on and so on. But what if we want to get serious about measuring personality? How do we turn these intuitions about the people we interact with into something quantitative? Once we do, how do we decide if what we've done has any validity?

What does it mean to have a chess personality?

As usual, chess is a fascinating domain for considering these questions. We have a lot of good quantitative data about players, we have a rich vocabulary for describing different aspects of chess positions, and we also have a lot of intuitions about how players differ from one another. I know I've brought up Fischer's "My 60 Memorable Games" here before, but it really deserves some special attention in this regard due to how well it describes how players like Keres, Petrosian, Spassky, and Geller each pose their own unique challenge due to their approach to the game. Part of what I enjoy about playing through classic games or watching current tournament play is seeing different chess personalities on display: Which players seem absolutely fearless and which ones are more willing to slowly squeeze the life out of their opponents? Perhaps more importantly, which one of those truly great players do I think I'm the most like?

This guy - it's definitely this guy.

Chess players clearly love thinking about that last question. There are many online opportunities to try and estimate your own chess personality, including offerings from chess.com (you can go check out chesspersonality.com), chessiverse.com (https://chessiverse.com/personality-test/), and a very nice recent blog post by Julian at Chess Engine Lab (aka @jk_182 on lichess) adopting a data-driven approach to measuring the style of GMs. What I want to do here is say a little bit about how we might try to estimate something intuitive, but complex and multidimensional like chess personality by unpacking how psychologists developed the tools we use to estimate personality. This will be just a brief overview of a rich and complicated topic that experts still argue about, but I hope it gives you some interesting food for thought with regard to how we can try to capture what's different about how different people play the game.

Chess personality categories from chesspersonalitytest.com

The OCEAN of Personality - Why are there 5 things in the "Big 5?"

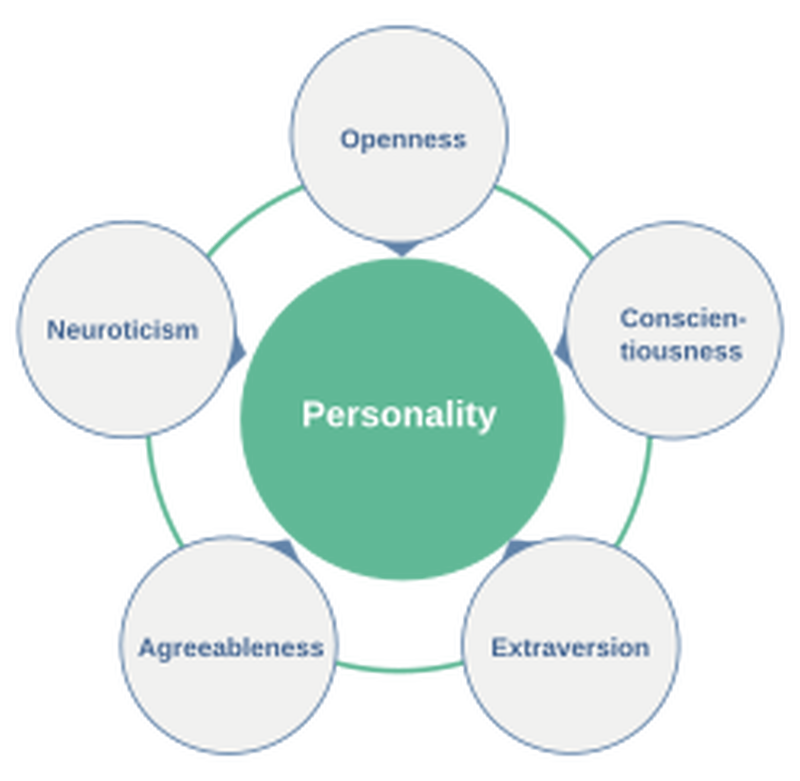

While personality psychology is not my area of expertise, I feel pretty confident in saying that the most widely accepted model of what we mean by personality is the "Big 5" Personality traits. The name refers to the 5 factors that make up the model, each of which represents some aspect of personality that individuals are scored on through the use of established surveys. Those factors are often taught to students using the acronym OCEAN, which stands for the traits of Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism.

By Original: Anna Tunikova for peats.de and wikipedia Vector: EssensStrassen - https://peats.de/article/big-five-die-personlichkeit-in-funf-dimensionen, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113609961

But wait a second: When I say "established surveys," how did these get established? And why are the OCEAN traits more widely accepted than other models? You might have come across a personality test called the Meyers-Briggs test, for example, which will give you a personality type based on 4 binary traits (intro/extroversion, thinking/feeling, sensing/intuition, and judging/perceiving). Why does that test have four things in it while the "Big 5" has, well, five? Come to think of it, how did the people who came up with either model (or any other alternatives) settle on a specific number of personality traits and specific descriptions of those traits? The answers to these questions have more to do with data science than they do with psychology, at least in my estimation. I say this because at the heart of these personality models (and many other similar attempts to measure something complicated about the mind) is the idea that there is some useful structure, or shape, in the data we can collect from different people when try to measure how they are different from one another. Briefly, here is a look at where the Big 5 personality model came from, which I think serves as a useful starting point for thinking about how we could try to define a chess personality.

A recipe for building a personality model

The first thing we have to do if we want to assign personality traits or categories to different people is come up with some things to measure to get us started. A model of personality begins with a set of measurements (in this case usually survey questions we ask people to answer about themselves) that we think will have something to do with the different ways that people act. If we're really building a model of personality from scratch, we have to assume we don't know a great deal about what we're likely to find, so we should make sure to include a lot of different questions so we don't miss anything. In terms of the history of personality psychology, this meant asking people to either describe themselves or others using a long list of over 150 different words that could describe different ways people tended to act: Would you say you are a lazy person? Are you funny? Do you often feel nervous?

Stock Image.

Here is the hard part about this step: When can you be sure you haven't left something out? Those 150 words or so sound like quite a lot, but that doesn't mean there isn't some collection of words we didn't think to include that might matter a great deal (maybe bookish should be in there, for example, or how about vengeful or delulu?). There is no especially satisfying answer to this question, unfortunately, so at some point we simply have to make a choice.

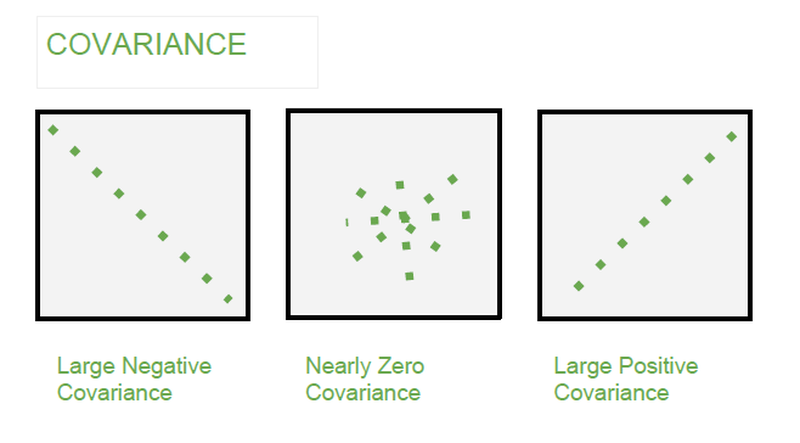

Armed with that data, the next step is to go looking for structure in the data we collect from many different people. But what do we mean by structure? What we often mean by this from a data science perspective is that we're interested in finding out how our different measurements vary together (formally, their covariance)- if someone says that they are lazy, does that have anything to do with how funny they said they are? Are there specific combinations of scores across these words that we tend to see over and over again, leading to "clumps" in our data? To the extent that this is true, it tells us that those qualities may refer to the same thing and so (1) We don't need to measure both of them (2) We might have learned something about core elements of personality.

Covariance examples from geeksforgeeks.com

Thankfully, there are many different statistical tools for asking questions about covariance and "clumpiness" across measurements, even when we have dozens and dozens (or more!) of variables we want to think about at once. These include tools like Principal Components Analysis, Independent Components Analysis, Manifold estimation techniques, k-Means clustering, and many others. In general, these tools give us a way to turn a large set of measurements into a smaller set by taking advantage of covariance relationships.

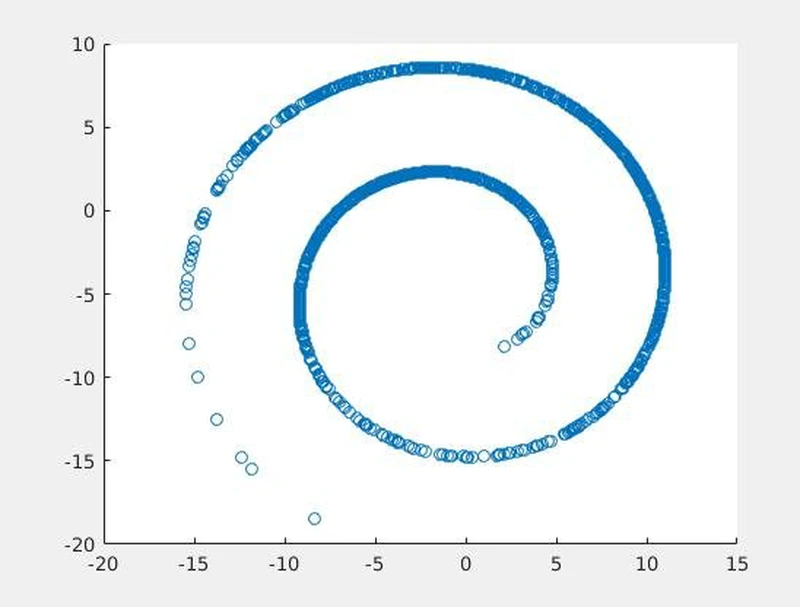

But here is the hard part about this step: How do we know what kind of structure to look for, especially with so many measurements? Most techniques for finding covariance, clumpiness, or whatever words you want to use to describe structure in rich data do their work by making some assumptions about the structure that might be in there. Let me show you one famous example below: If we asked people to respond to just two questions and plotted the two values each person gave us on an xy-axis, let's imagine it makes the very interesting shape below.

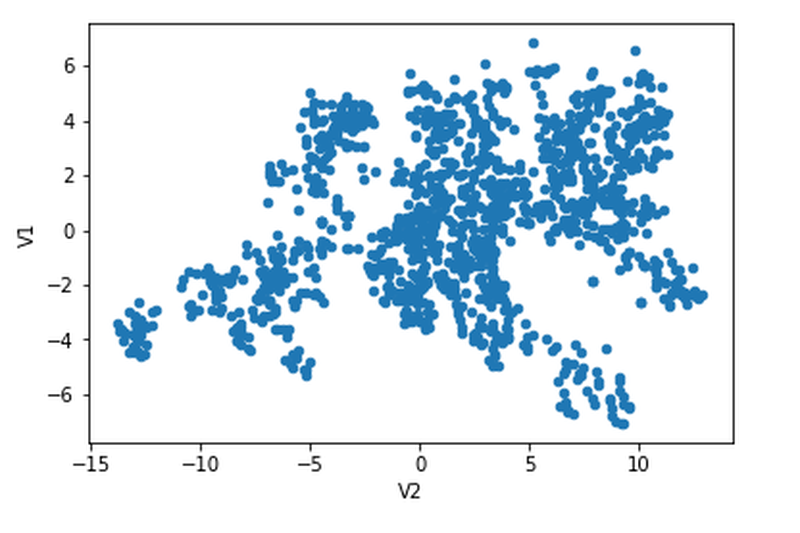

If you were to try and find a simple correlation in this data, you'd find out that the two variables either weren't correlated at all, or were correlated only weakly with one another. If you stopped there, you'd have a nice, tidy result you could report, but you also would have missed the beautiful spiral (or "Swiss Cake Roll" as this is sometimes called) that truly captures the clumpiness of this dataset. Again, there is not a great solution to this other than to try some different things out and ultimately make the best decision you can. Another decision you may have to make will be how many pieces your final structure will have. If you look at the data I've plotted below, how many clumps do you see? When I ask students about this in the Machine Learning unit of one of my classes, I usually get a range of opinions: Maybe 6 or 7? Maybe as many as 12? It all depends on how big you're willing to let the clumps be and there isn't necessarily a clear right answer for complex data sets with many more variables.

In the case of the Big 5, examining paricipants' answers about dozens of different personal qualities with a technique called factor analysis led several groups (in some cases using different questions as a starting point) to the same conclusion that 5 "factors" captured the covariance between survey questions. By looking at survey questions that contributed most to those factors led us to the OCEAN model that has seen steady academic use ever since.

So can we do this for chess?

That is a very brief (but perhaps too long for a blog post!) history of how psychologists built a model of personality. Now, the real question that is the focus of this article: Does this suggest a way to construct a good model of what a chess personality? To talk through what I think is interesting and challenging about doing so, I want to consider each step in the recipe for a personality model I described above to see how this would work (or maybe not work) for chess.

What should we measure?

I said that personality models start with decisions about what to measure and chess presents with a range of interesting possibilities. In @jk_182's recent post, "playing style" was determined by a range of different game statistics that captured how specific pieces were moved during a player's games. Are you a player who is willing to forego castling in favor of a strong attach? If so, that might be something we can measure the frequency of throughout your playing career as part of your chess personality. This sounds like a decent start, but with the usual caveat that we'll want to include as broad a range of moves as possible to be sure we don't leave out important behaviors.

How often you move each pawn and where they tend to end up is one way to try and describe your playing style.

But there is something I can't help but worry about and it has to do with one of the big differences in chess personality between myself and (for the sake of argument) let's say GM Hikaru Nakamura: Part of Hikaru's "chess personality" is that he is very, very, good and I am comparatively very, very bad.

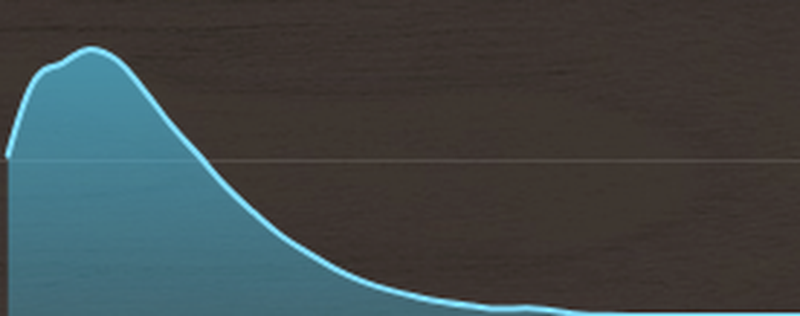

One of us is all the way to the right of this distribution and the other...isn't.

But wait? Is playing strength actually a part of chess personality? This is something that I suspect may be tricky about determining a chess personality relative to psychological models of personality. In chess (unlike personal qualities) there are objectively better or worse moves for a player to make. Some of my playing history of making various kinds of moves may reflect my chess personality, but some of them also reflect my lack of titled-player skill. This might mean that when we try to learn about the factors underlying chess personality, some of those factors are actually about being good at the game, which doesn't seem quite like what we mean.

How do we separate chess skill from chess personality?

There are a few ways we might try to avoid this problem and get to a way to determine your chess personality that isn't dominated by your playing ability. One possibility is to develop different models of chess personality for different classes of players (GMs get their own model, IMs get their own, and patzers get still another). But here are some ideas for thinking about chess personality without separating players into these kinds of skill classes.

1) Use openings!

If we want to separate skill from personality, one way to think about this is to assume that personality affects how you choose between moves that are objectively equal. If one player chooses the best move in a position and another tends to choose a worse one, it's not obvious that we should call that a personality difference. The trouble is that in many positions there is a relatively narrow set of possible moves that are of equal worth. But when are there lots of options of approximately equal value? On the first move!

We all know that there are e4 people and d4 people.

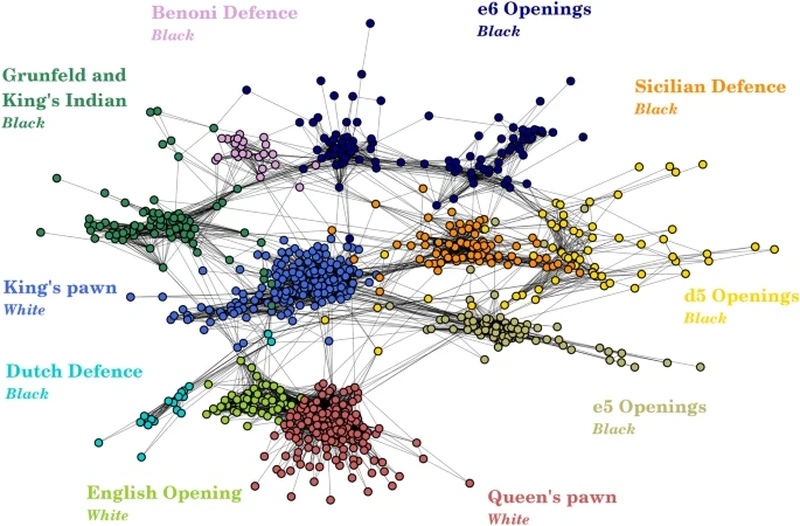

Opening choice turns out to have some neat clumpiness to it, too. In a relatively recent paper by De Marzo & Servedio, the authors went looking for structure in data describing the opening play of a large database of Blitz players. Briefly, their goal was to identify families (or clumps) of openings based on player co-occurence: If lots of players like to play the same two openings, that's a good hint that these might be part of a meaningful opening family. Below, you can see the clusters they identified in their data, which could be used to identify players' personality based on opening repertoire across these groups.

Figure 1 from De Marzo and Servedio showing the different families of opening clumps they discovered from player-opening Blitz data.

2) Use a forced-choice survey

This next idea is a little bit tougher, but might also be a way out of the skill/personality conundrum. While there is often an objectively best move in a given position, it can also be the case that there are at least 2 or 3 moves that all keep the evaluation at about the same place. Which one should you pick? Perhaps the decisions people make in those situations are down to taste, or personality. My suggestion here is that one could possibly build a short survey using positions like this and present players with the set of equally good moves to choose from. This isn't far removed from collecting moves from a huge library games as we're still interested in which moves players tend to favor, but we'd be constraining that data to focus on distinguishing between equally-good choices.

3) Use puzzles!

This last one is perhaps a little dubious as a way to disentangle skill from chess personality, but it's something I've been curious about for a while. Rather than trying to avoid situations where there is a clear best move, maybe those are exactly the situations to consider! Specifically, performance across different puzzles may be a useful means of working out what kinds of ideas tend to occur to players more readily as a way of characterizing their style. Yes, stronger players will be better at puzzles in general, but perhaps there will still be room to see what kinds of moves they tend to find the hardest to come up with when they know there is a best path.

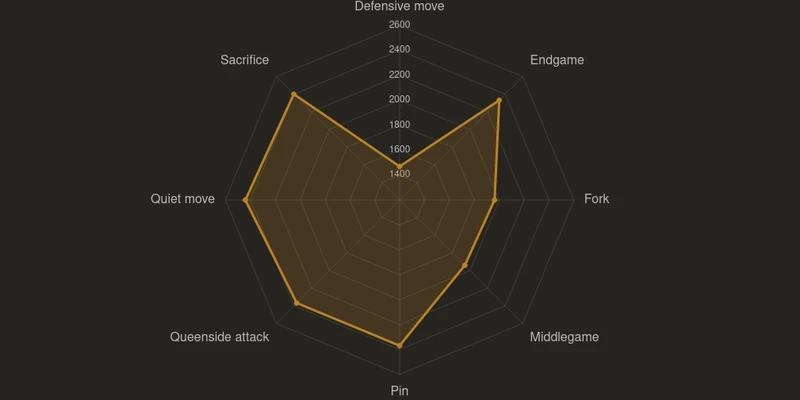

Interestingly, Lichess (like other sites) has an existing classification of puzzle types and also incorporates these into a Puzzle Dashboard graph I can't help but find intriguing. Using different players' performance across these different categories would potentially be a neat way to determine a "chess personality" we could compare to other data sources (an idea I raised in my blog post about predicting puzzle difficulty). Now this does raise the question of how meaningful those puzzle types are in the first place (its own neat data analysis question), but still a potentially fun sandbox to play in.

How many pieces are there to chess personality?

Once we settle on a strategy for measuring personality with a lot of variables that we think are meaningful, there are still a lot of questions to think about. In particular, how do we go looking for structure in those measurements? Do we think chess personality is meaningful to talk about in terms of continuous dimensions (traits like we find in the Big 5) or categories (like the pseudoscientific Meyers-Briggs test - the scale isn't valid, but there isn't anything inherently wrong with categories!)? In either case, how many types of personality should we go looking for? If we're lucky, the data may give us some big clues, but in analytic problems like this we're often not especially lucky.

This is a setting where I'd say we may have to rely a lot on some domain knowledge from people who have known a lot of players. This also applies to the problem of deciding what to call the various factors or clusters we identify in our data. It's lots of fun to label ourselves as "Romantic" or "Defensive" but the data may present us with some combination of playing choices that are harder to pin down. In such cases, landing on a good interpretation is as much about finding good ways to communicate what you're seeing to others as it is about thinking about co-variance, clumpiness, and information criteria.

Closing thoughts

Like so many interesting questions about the mind, pinning down what a "chess personality" might be is a little maddening and potentially a lot of fun. It also has the potential to start a lot of good conversations, maybe a few solid arguments, and make room for a lot of neat data science projects. If you find these topics interesting, I'd encourage you to browse the ever-increasing library of available games and player data (including the remarkableLichess Open Database) to see what you can see. While perhaps we shouldn't take the idea of a chess personality especially seriously, it's also a nice excuse to try and understand one little corner of human behavior quantitatively.

I know this one was a long one, but if you've made it through to the end I hope you enjoyed it! I'm hoping to have some more posts soon focusing on some smaller topics, so stay tuned for more Science of Chess in the near future.

Support Science of Chess posts (and others)!

Thanks as always for reading! If you're enjoying these Science of Chess posts and would like to send a small donation my way ($1-$5), you can visit my Ko-fi page here: https://ko-fi.com/bjbalas - Never expected, but always appreciated!

References

De Marzo, G., Servedio, V.D.P. Quantifying the complexity and similarity of chess openings using online chess community data. Sci Rep 13, 5327 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31658-w

Link to @jk_182's post "Identifying the Style of Different Players" - https://lichess.org/@/jk_182/blog/identifying-the-style-of-different-players/WnfPnBli

McCrae, RR; John, OP (June 1992). "An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications" (PDF). Journal of Personality. 60 (2): 175–215. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x. PMID 1635039. Retrieved 2025-03-17.

Link to "The Personality Brokers" by Merve Emre, a fascinating account of the development of the Myers-Briggs Personality Test https://app.thestorygraph.com/books/687a7765-da8c-4ddc-b6f8-2ae616417dae

You may also like

ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess: Proving yourself wrong

The best players know it's not enough to be right, it's also working hard to find out when you're wr… CM Sohamchess64

CM Sohamchess64A Golden Cage

A perspective towards improvement. Lichess

LichessShould I report this?

Ever encountered a user misbehaving on Lichess? Check out if and how to report them. IM MatBobula

IM MatBobulaHow Petrosian Teaches You to Defend Like a Pro

Attack is everywhere. You can find tons of videos, articles, and games about how to attack. Tal, the… NDpatzer

NDpatzer